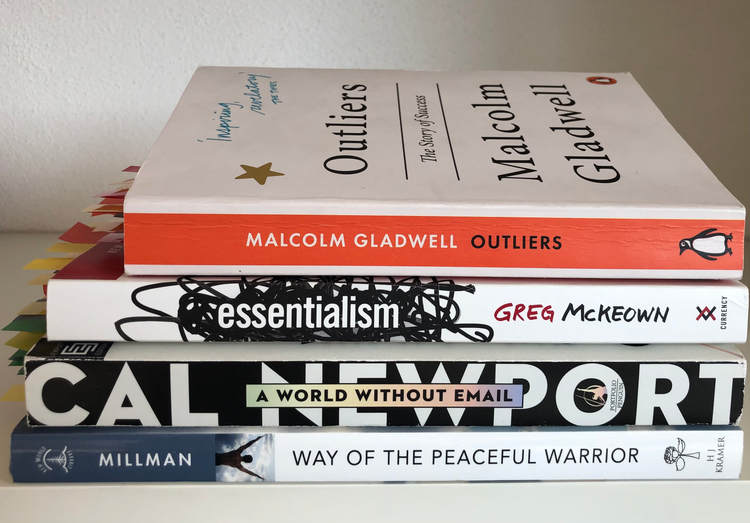

March's reads

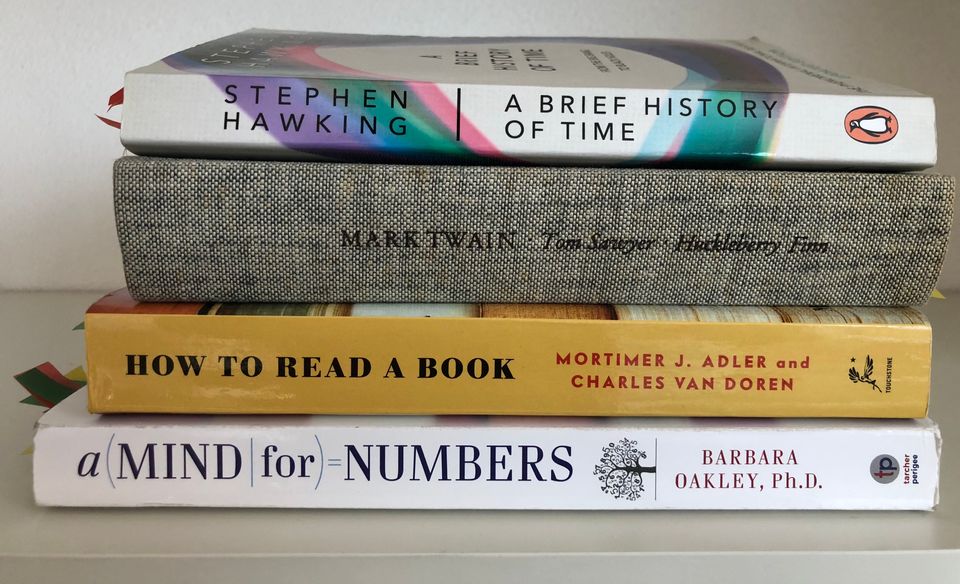

Mark Twain, Adler & van Doren, Stephen Hawking, Barbara Oakley

This March 2022, I finally finished a challenging read, How To Read A Book, by Mortimer J. Adler and Charles van Doren. Besides this, I also traveled to old America by reading Mark Twain’s The Adventures Of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

How To Read A Book, by Mortimer J. Adler and Charles van Doren

This book has been on my (imaginary) reading list for a long time; I think I came across this praised work two-ish years ago. But it was not until this year’s beginning that I bought it, together with many other books. Some of them I have read in the two previous months, January and February, but with this book, it took longer.

Though I started reading it at the end of January, it was not full-time. Partly, this was because it was a challenging read and somewhat because I was intrigued by other books. Anyways, this classic book really tells you how to read a book. It does so by covering different reading types (less active vs. more active reading), grasping a book quickly (e.g., skimming, reading the table of contents), and offering practical rules throughout.

The challenge in reading this book was due to its wording. While I thought that my reading was quite good, this work showed me otherwise (which is already a sign of a good book!). However, my challenge in going through the 300 and more pages was aligned with one of the central ideas: Only books beyond your level can teach you.

This book is recommended for anybody wanting to get more out of the reading sessions.

Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain

After finishing the last read, I traveled to 19th century America. Author Mark Twain has crafted a remarkable novel about the adventurous boyhood of two equally daring boys. Besides the amusing, wild, and dangerous adventures the two boys experience, the book is also a good window into another time.

Because it is set around 1840, the world it plays in is still of racism against black people, often denounced and portrayed as dumb. Further, the children are often beaten by their teachers and parents, which thankfully is no longer practiced nowadays. Further but smaller sections contain social criticism regarding the in-equality of women, long-lasting feuds, and the role of labor.

Besides (or is it because of?) these woven in critical sections, the two books, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, were a captivating read. I am envious of the adventures that they got to experience and the sheer unbelievable amount of time they spent being in nature. They go fishing, treasure hunting, form a band of robbers, become pirates, break away from home, witness a murder, and much more.

This book is a superb candidate for anybody looking to escape to a seemingly more adventurous time.

A Brief History of Time, by Stephen Hawking

For more than 30 years, Stephen Hawking held the same position as Sir Isaac Newton, three hundred years before him. His accomplishment is even more remarkable because his writing is outstandingly accessible. This fact is demonstrated in many books he has written on the universe, with A Brief History of Time being a worldwide bestseller.

In this 200-is pages work, Hawking takes us on tour through the universe: how it might have begun, why it might currently be how it is, and how it might become. This journey is fascinating, as it sheds light on many topics fundamental to our being. Additionally, it’s also an appealing read for anybody interested in Physics and Astronomy.

Hawking’s travel visits influential ideas that came up throughout the centuries, such as the orbiting of the sun around the earth, the universe’s expansion, the relativity of time, and, my favorite, gravity. No matter what topic is being explored, the reading remains down to earth, and technical terms are explained clearly whenever they are used. This portrayal should not give the impression that the book is somewhat dumbed down; no. In contrast, the book will require most readers’ attention.

However, as often is the case with challenging material: it sticks and we get more out of it than had we mindlessly glanced through.

Favorite quote:

[…] Ever since the dawn of civilization, people have not been content to see events as unconnected and inexplicable. They have craved an understanding of the underlying order in the world. Today we still yearn to know why we are here and where we came from. (p. 15f.)

A Mind for Numbers, by Barbara Oakley

Barbara Oakley is one of the instructors of Coursera’s highly popular and top-rated Learning How to Learn course. In her book, which equally teaches you how to learn, she lays the focus on math and the sciences. Over the course of 250 pages, she takes the reader through different concepts related to studying.

One of the first concepts covered is the difference between focused mode attention and diffuse mode attention. The former, which we all feel when we concentrate intensely on a single subject, is what we employ regularly. But, as Professor Oakley shows, it’s highly beneficial to use diffuse thinking, too. In this mode, the thinking processes tap into the brain’s vast diffuse resources, potentially yielding genuinely creative solutions. Combining the two ways by first focusing on a challenging situation and then letting the (subconscious) diffuse mode ponder on it can make the difference.

This is not the only novel idea that I encountered. However, now that I am aware of this difference, I often deliberately switch between the modes to gather as many ideas as possible. The same can be said of another strategy, active recall. I had encountered it before in Scott Young’s Ultralearning but had not actively used it. After reading about this technique again, I now employ it during my daily reading and learning sessions. It’s a simple way to improve how much sticks.

The books focus on math and science, so it’s a good recommendation for anyone active (either as a student or teacher) in these fields. However, the ideas contained within are relevant for anybody from any domain; the presented techniques apply to everybody’s learning.

Favorite quote:

We develop a passion for what we are good at. The mistake is thinking that if we aren’t good at something, we do not have and can never develop a passion for it. (p. 148)