June's Reads & Books for July

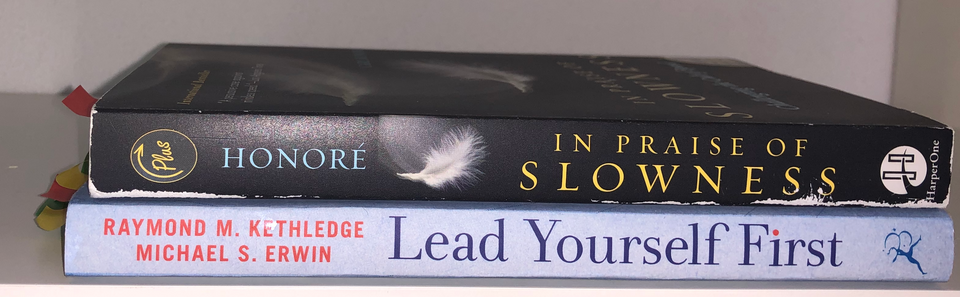

Carl Honoré, Raymond M. Kethledge & Michael S. Erwin

As in July, two great works came across my reading table. Both books explore two oft-neglected aspects of our lives: being slow and being alone. Enjoy reading them!

In Praise of Slowness, by Carl Honoré

The world we live in values speed. The untold motto we all unconsciously subscribe to is doing things faster. Getting faster from A to B (as if the outside of A and B is just an annoying necessity to traverse), getting in shape faster, and working faster. Going fast all the time is as limiting as being slow all the time; one needs to find the tempo giusto. That is what author Carl Honoré set out to do with his book. Over several chapters, he covers how we can introduce more slowness into our hectic lives.

The first thing we can adapt is to eat slower, eat more mindfully. While a quick food stop at a fast food “restaurant” is tempting, what we get from devouring such junk is repelling. We eat more (because we do not get the stop signal from our stomach in time), we eat unhealthily, heck, we often can’t even name the ingredients. In contrast, by preparing, as often as we can, our dinner ourselves, we get to know what goes into our meal. By manually cutting onions, peeling potatoes, and seasoning meat we get a chance to take a step back from the busy, scheduled lifestyle we’ve come to see as the norm. Cooking can be an escape.

In the successive chapters, Honoré guides us through further aspects of our lives that we can decelerate. For example, there’s a chapter devoted to slowing (i.e., calming) the mind. Here, meditation, an age-old technique practiced by countless leaders, is one of the most-accessible „tools“ we can use. Besides focusing on our bodies, we should also slow down the education of the next generation. Instead of cramping our kids’ schedules to the maximum, we must give them space and, critically, unstructured time to explore the world. Contrary to what we might suspect, giving our offspring a slower education does not have any negative impact on their future. Quite contrary, by exploring a topic at a slower pace, they develop a more throughout understanding of the subject.

I found this book to be a welcome and refreshing read. By illustrating the benefits of a less-full lifestyle, Carl Honoré does an excellent job at pursuing us to decelerate our lives. And, by letting people like you and me talk about their experiences, he makes the reader want to implement slowness quickly.

Lead Yourself First, by Raymond M. Kethledge and Michael S. Erwin

After exploring the benefits of walking by reading A Philosophy Of Walking by Frédéric Gros, I looked for a chance to dive deeper into one of walking’s characteristics: being alone. In Kethledge and Erwins’ work Lead Yourself First, I found countless examples of people who used solitude to grow. As an example, take the Burmese heroine Aung San Suu Kyi, who was repeatedly confined to year-long house arrests. Instead of falling into despair, the strong woman used the forced timeout — away from her family in England — for fruitful contemplation. Spending more than fifteen years(!) under house arrested, she developed the underlying philosophy for her political movement: metta, meaning helping others even if they are your opponents. Over her prisoner years, she had the time to spend countless hours in meditation, practicing active contemplation. The long years of practice would finally pay off when in 2015, her National League for Democracy won the nationwide elections with sweeping success.

The tremendous development, being repeatedly imprisoned to leading a democratic party with a strong underlying philosophy of metta would hardly have been possible without her practical use of solitude. It’s therefore no wonder that the authors define solitude as a subjective state of mind where the freedom from others’ inputs allows one to work on tough problems (c.f. p XX in the introduction). Throughout history, powerful and everyday people have used this tool to gain clarity (e.g., General Eisenhower), emotional balance (e.g., President Abraham Lincoln), courage (e.g., Martin Luther King), and creativity (e.g., Lawrence of Arabia). Throughout the book, Kethledge and Erwin introduce us to the stories of those people, showing how they used time alone to ponder the situations they faced.

As the book’s subtitle, Inspiring Leadership Through Solitude, hints, it is especially leaders in any position who benefit from the productive use of solitude, or thinking time. However, since we are all leaders at some point in our lives, and since we always lead ourselves, anybody benefits from reading the work.

Favorite quotes:

“[s]olitude is not the reward for great leadership. It’s the path to great leadership.” (p. 137, from interviewing Professor Brené Brown)

&

“Society did not make a considered choice to surrender the bulk of its time for reflection in favor of time spent reading tweets or texts.” (p. 181)